Disclaimer: While strength training has numerous benefits, individuals with hypertension should consult their doctors before starting a new exercise program. When performed with proper technique, avoidance of Valsalva, and gradual progression, safe strength training lowers blood pressure. Always exercise under proper guidance, particularly if you have severe hypertension or other cardiovascular conditions.

Could spiking your blood pressure with exercise actually lower it the rest of the time?

That’s a weird way to think about exercise, because for many people with hypertension, there is a fear that high blood pressure makes exercise dangerous1. From their own time searching the internet, and even from conversations with their doctors, they have a very reasonable worry that they need to avoid letting their blood pressure get too high. Unfortunately, this fear can keep people from engaging in exercise that can actually help their hypertension!

Now, it is true that extreme increases in blood pressure can increase our risk for vascular injuries like strokes. Fortunately, it’s pretty easy to avoid such extreme increases by keeping the loads we lift to more manageable levels, and by avoiding the “valsalva” maneuvre or bearing down and holding our breath.

But even with those precautions, blood pressure will still go up momentarily while we lift weights.

I’m going to make the case that this is actually a good thing!

It’s OK for heart rate and blood pressure increase during exercise.

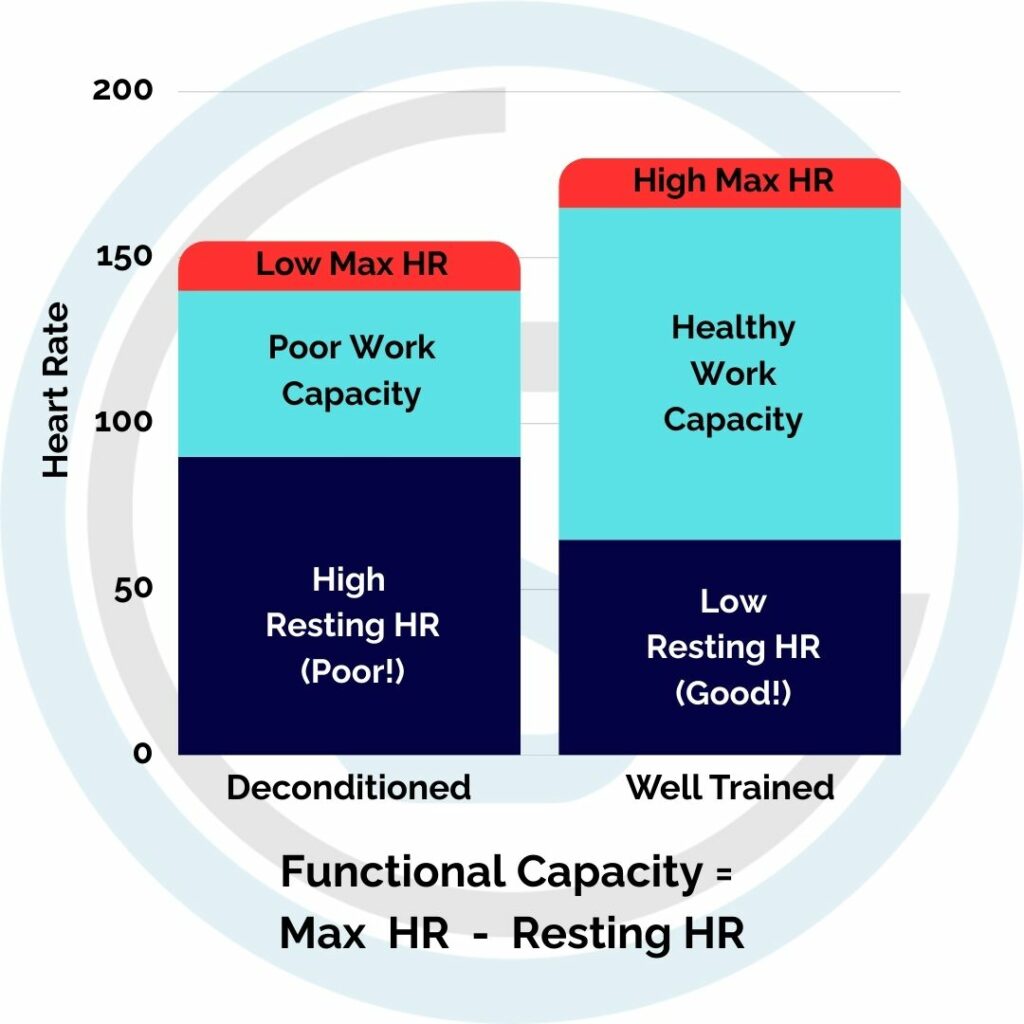

Let’s draw an analogy from another important metric of health: heart rate (HR). A low (unmedicated) resting heart rate is an excellent predictor of your longevity2. We are literally more likely to die from all causes, including heart disease and cancer, if we have a higher than ideal resting heart rate.

This is because a low resting HR is a sign that your cardiovascular system is having an easy time delivering oxygen and nutrients to your body. A high resting heart rate, by contrast, indicates that your circulatory system is having to work hard to meet the body’s needs even when you are at rest – not good!

Our maximum heart rate (the rate we could achieve with maximum effort exertion) is largely a function of age. For a 40 year old, it might be 180 beats per minute, while for an 80 year old it’s just 140 bpm. And so if that 80 year old’s resting heart rate is 90 beats per minute, that means that they are constantly living at around a 65% effort (90/140=~0.65). Life, in other words, is simply more physically difficult as the gap between resting heart rate and max heart rate shrinks.

So it’s in our interest to keep our resting heart rate low. In fact, low resting heart rate is an excellent proxy for VO2 max, which itself is an indicator of aerobic fitness and a powerful indicator of longevity and mortality risk. Specifically, you want a large gap between your resting heart rate and your maximum heart rate, which equates to a high VO2 max3.

To lower your resting heart rate, you need to raise it during exercise.

There are many other similar parallels. If the most your legs can lift is 200 pounds, but you weigh 180 pounds, then your legs are constantly having to deal with 90% of their maximum capacity just to get you around, which is very stressful. This would be like your car redlining it’s RPM’s just to get to the grocery store and back – your car would be on its last legs! And one of the easiest ways to make life easier for your legs is to load them with strength training. By stressing them acutely, we can increase their peak strength significantly. If those same legs can lift 300 pounds 2 years later, now your 180-pound body weight requires only 60% of your strength to move, making life much more comfortable, and actually reducing the stress on your body in day-to-day activities. And if you manage to reduce your body weight to 160lbs during those two years (thanks to expert nutrition coaching), now you only need to use 50% of your total strength to get around, making life even easier!

This is the key insight: Momentary increases in stress from exercise (elevated heart rate, mechanical tension, metabolic stress, and even elevated blood pressure), improve the body’s fitness and actually reduce the chronic stresses our body feels day to day.

Raising your blood pressure during exercise leads to lower blood pressure overall.

This turns out to be true for blood pressure as well. The real harm of elevated blood pressure has less to do with any one acute spike in the moment, and more to do with the cumulative effects of chronically hypertension. When our blood pressure is always a bit high, many of our organs experience a constant, low-grade stress, from our kidneys to our brains. The whole circulatory system stiffens and begins to work less effectively.

By contrast, when we have a generally low blood pressure that is elevated significantly for brief periods as we exercise and play sports, the effect is that our blood vessels become more flexible, not stiffer, and our circulatory system becomes more efficient at delivering nutrients to your tissues. This is why strength training lowers blood pressure over time and has the potential to reverse hypertension4!

Proper nutrition helps strength training to lower your blood pressure.

Instead of needing to be afraid to lift weights, people with hypertension actually have even more to gain from strength training! By moving slowly with moderately challenging weights, and controlling our breathing to avoid bearing down, we can reduce the risk of a truly dangerous increase in pressure. And by consistently exposing our body to brief and acute challenges to the vascular system, we can improve its health and pliability over time. In this way, strength training lowers blood pressure and reducing our risks for stroke, kidney damage, and cardiovascular events.

Finally, on top of all these mechanical benefits, strength training of course has the well established effect of improving our sensitivity to the hormone insulin. Resistance training truly is medicine5! By improving the metabolic health of our muscle tissue, we reduce the need for excessive insulin production. Insulin has many benefits, but in excess, it can lead to stiffening of the arterial wall, which increases blood pressure to dangerous levels. By keep our metabolisms healthy, we reduce fasting insulin levels and interrupt this problematic stiffening of the arterial wall.

This conversation would of course be incomplete without a nod to the benefits of healthy eating. Losing visceral fat is the most reliable tool in the quest to improve hypertension and our risk of cardiovascular disease. Resistance training can be accomplished in just an hour of total exercise per week with great effect, but eating correctly really does require a shift in lifestyle that can be very challenging to achieve alone. This is where the help of a behavior modification expert can be invaluable, like Kelly Lee at ThinkWellNutrition.com.

Conclusion

In summary, you do NOT have to be afraid of strength training if you have high hypertension. Strength training may be the best way to lower blood pressure over time6! Consult with your health care provider before starting a program, and whenever possible, seek out expert exercise instruction to ensure you aren’t pushing yourself dangerously as you seek to improve your health with a joint-friendly exercise program.

- “It is the fear of exercise that stops me” – attitudes and dimensions influencing physical activity in pulmonary hypertension patients – PubMed ↩︎

- Resting heart rate and the risk of cardiovascular disease, total cancer, and all-cause mortality – A systematic review and dose-response meta-analysis of prospective studies – PubMed ↩︎

- Estimation of VO2max from the ratio between HRmax and HRrest–the Heart Rate Ratio Method – PubMed ↩︎

- Resistance exercise lowers blood pressure and improves vascular endothelial function in individuals with elevated blood pressure or stage-1 hypertension – PubMed ↩︎

- Resistance training is medicine: effects of strength training on health – PubMed ↩︎

- Impact of resistance training on blood pressure and other cardiovascular risk factors: a meta-analysis of randomized, controlled trials – PubMed ↩︎